While deeply involved in Marzanno and Waters (2009), I had the opportunity recently to attend a recent high school orchestra concert. It is, thus, logical to reflect on instructional leadership as similar to the experience of developing a musical harmony that mingles concepts from Marzanno and others such that we have a cohesive, but responsive approach to student achievement. While many would assume that a musical composition is static in nature, it is in fact a highly dynamic endeavor that yields different results when factors of acoustics, instruments, expertise, and the emotions behind the score spread and mix upon the stage. In this most recent concert, graduating seniors and year-end farewells set the stage for an once-in-a-lifetime version of a particularly complicated flute solo that was masterfully presented as a farewell tribute to the conductor and teacher. Much like an orchestral piece of music, the notes and staff only told a very course version of the story behind the music. The instrumental process that yields note dynamics, breath control, posture, precision (or lack thereof), and a weaving of expertise results in a performance – an experience.

In much the same way, our current approach to achievement is more about looking at the music rather than reflecting on the elements of the performance. This emerges from an issue of granularity. When we look at a large boulder, we see the surface and get general information regarding the face of the boulder and maybe some insight into the color, texture, and weight of the object. Summative testing is akin to this global view where we derive scores and assess program by examining the accomplishment of large groups of students. What we don’t see, and teachers often reflect on this, is the material just below the surface. If we begin by breaking the boulder into smaller and smaller pieces, we reveal the details of the musical composition – the subtleties, the nuances, the complexity. Ultimately, when we arrive at grains of sand, we have a very complete picture of the boulder – even though it is a boulder no longer.

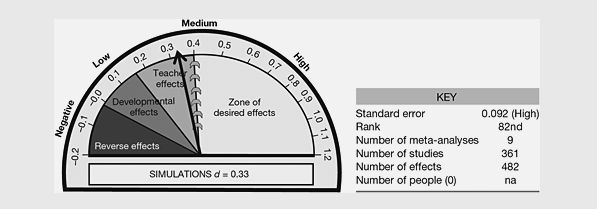

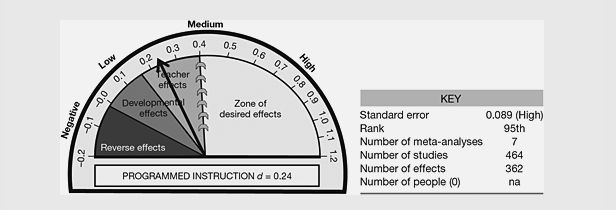

Formative testing is largely about breaking the boulder of education into grains of accomplishment and by looking with this level of scrutiny, we greatly improve our chance of impacting performance in a positive way. The key is achieving a high degree of granularity while not distracting from our primary task of achieving broad spectrum learning goals. Formative assessment meets this criterion and provides an instructional strategy that not only focuses teachers on viable instructional objectives, but also informs both students and teachers about their progress toward accomplishing the same. The musical score transcends the subtleties of the dynamic factors of performance by forming the foundation of the presentation. In this way, we have a metaphor for the core structures that Marzano and Waters (2009) propose in the form of nonnegotiable goals. Their reflections on the inadequacy of NCLB and other summative high stakes measures gives way to a formative system of measures aimed at developing a “value added” approach. This is consistent with multiple recent research endeavors including Hatie’s (2009), where formative feedback to teachers regarding their efforts with students yielded the 3rd highest effect rating on overall achievement – approximately d=0.90.

The challenge is not about curriculum, while it is valuable to continue curricular development processes as we currently do. The issue is the creation of common formative assessments that match the curriculum and provide for close scrutiny of granular accomplishment. With Marzano and Waters (2009), we find a proposal for a “value added” approach to education that calls for both horizontal and vertical alignment with a common scale of measurement for formative assessment tools used along the way. Arranged according to topic areas and grade levels, this proposal leads to a comprehensive look at how a curriculum should emerge in the classroom, the way in which we test pre-operationally for its introduction, and the way in which we report developmental progress along a scale toward achievement of that curriculum.

But they may not be going quite far enough in addressing the thousands of small bits that constitute a comprehensive child-centered approach to personal development that also addresses the development of character and emotional intelligence. Education continues to stare at the boulder and misses this aspect under the surface. A value added approach may also miss many of the grains of sand by sifting and looking only for the specs of interest.

If we really want to form sand castles, we need to address how all of the sand can be cemented together into the complex structure that is a whole “person.” While I value assessment as important, it does little to address the complex nature of a child and the nuances of how the the score becomes a performance.

References

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge.

Marzano, R. J., & Waters, T. (2009). District leadership that works: Striking the right balance. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.